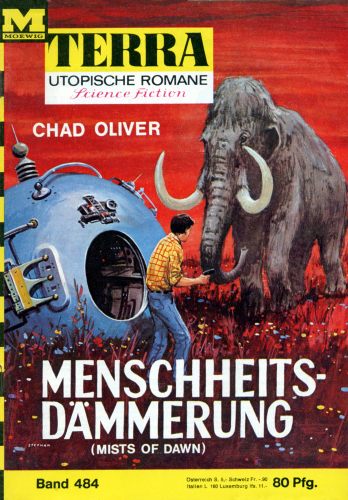

Chad Oliver : Menschheitsdämmerung (Mists of Dawn)

Terra SF 484, 14.10.1966

Deutsche Erstausgabe

Originalausgabe 1952

Aus dem Amerikanischen von Birgit Bohusch

Titelbild : Karl Stephan

Dr. Robert Nye, Wissenschaftler des Raketentestgeländes White Sands in New Mexico, hat in jahrelanger privater Arbeit eine Raum-Zeit-Maschine erschaffen. Doch als es darum geht, das Gerät zu inspizieren, passiert Unvorhersehbares: Die Maschine wird aktiviert, und Mark, der Neffe des Wissenschaftlers, wird aus dem Heute in eine entfernte Vergangenheit geschleudert. Der junge Mann erreicht ein eiszeitliches Land, in dem Neandertaler und Cromagnonmenschen um die Vorherrschaft kämpfen, und wird in die Konflikte mit einbezogen. Mark sieht sich gezwungen zu töten, wenn er überleben und den Weg zurück ins 20. Jahrhundert finden will.Klappentext der UTOPIA CLASSICS-Ausgabe

Ein wirklich gelungenes Jugendbuch, ausnehmend schön und unaufgeregt geschrieben. Mark, der Held der Geschichte, setzt sich vorurteilsfrei mit den Cro Magnon- und Neandertaler-Gesellschaften auseinander, ohne irgendeinen Snobismus des Zivilisierten heraushängen zu lassen. Vielleicht heutzutage von der Sicht der Dinge etwas überholt, aber für Kinder und Jugendliche immer noch unheimlich geeignet.

Chad Oliver (1928-1993) war im Hauptberuf Anthropologe, er wusste also, wovon er schrieb. Das merkt man dem Roman auch an, gerade in den Details erscheint er mir als Laien recht stimmig und präzise. Die amerikanische Originalausgabe enthält auch ein längeres Vorwort, das bisher in keiner der deutschen Ausgaben enthalten ist :

I: How to Travel in Time.Vorwort, zitiert nach dem SF Gateway-eBooks

If you were asked to name the basic drives and preoccupations of this strange creature called man, your answer would no doubt depend upon how much psychology, history, economics, and what-have-you that you had been, or had not been, exposed to. It is a safe bet, however, that you would not be tempted to list time travel among man’s strongest yearnings.

And yet, stop a moment! It is curious indeed how much of our time is taken up with exactly that—the vague desire to travel through time. You are perhaps skeptical, and rightly so. You are possibly inclined to protest that you, personally, never had the foggiest notion of traveling in time. But consider: what were the games you played as a small child? Did you pretend that you were an office worker, or a Certified Public Accountant? You may have done just that, for all I know, but I would hazard a guess that you spent many more hours playing Cowboy and Indian, or Kings and Queens, or, like Tom Sawyer, imagined yourself to be the Black Avenger of the Spanish Main. These days, in a world of science, you have no doubt fancied yourself living in the future as well, in a civilization of silver spaceships and the fascination of other worlds.

What is all this but time travel? Somehow, man is never satisfied with what he is. He always wants to go somewhere else, be something different. He imagines himself in another age, made more romantic by the gulf of time. It is not beyond belief that children of the future will amuse themselves by playing that they lived in that long-ago and wonderful period of the 1950’s through which we ourselves are living.

Perhaps responding to this old fantasy of mankind, science fiction has long concerned itself with time travel as a major theme. Ever since H. G. Wells wrote the classic The Time Machine, writers have been having a lot of fun traveling through time.

It would be untrue, however, to present the idea of a time machine as anything but what it is, an intriguing literary device, part of the bag of tricks of the science fiction writer. We have no time travel in the sense of actually having a time machine at our disposal, and thus there is no such thing as a “science” of time travel. This is not to say that such a device is impossible; it is simply that we know nothing whatever about it.

The best we can do is guess.

Nevertheless, we need not be discouraged. There is a way we can travel through time, in fact as well as in fiction. The human mind is a time machine that can carry us backward or forward at will, and we have far more than guesswork to guide us in our travels.

Science fiction, like everything else in the world, has changed. In modern science fiction, the emphasis, the focus, of the story is far different from what it once was. It used to be, back in the days of Jules Verne, that writers were concerned with the all-important how. How could a ship travel from the Earth to the Moon? How could a man travel backward in time? This is still an important factor, but a new element has been introduced. The question today is not so much how the characters got where they were going, but rather what happened after they got there?

Many modern science fiction stories, in other words, start where the old ones ended. This is not to imply that the social sciences have replaced the physical sciences as a framework for fiction—surely with actual space flight almost upon us this is not the case—but simply that science fiction has acquired a new dimension. We still have our technology and our physics and our machines—but now we include human beings as well.

So it is that the real science in this book is not time travel at all. Instead, it is a science called anthropology.

II: What Is Anthropology?

A surprising number of people, if they have heard of anthropology at all, have only a confused impression that it has something to do with old bones and dinosaurs. There is some excuse for connecting it with bones, and none at all for dragging in the dinosaurs.

Anthropology is a rather large word, but it is nothing to be afraid of. Anthropology is the science of man, the science of you and me. As Dr. Clyde Kluckhohn once phrased it, “An anthropologist is a person who is crazy enough to study his fellow man.” More specifically, anthropologists concern themselves with groups of men and their cultures.

There are two main divisions of anthropology, physical and cultural. Physical anthropology concerns itself primarily with man as a physical animal—his skeleton, his race, how he is put together. Cultural anthropology deals with aspects of human behavior beyond the physical level—how do peoples live, how are societies put together, what do people do, and what have they done in times past. The further divisions of anthropology—ethnology, ethnography, applied anthropology and the rest—need not concern us here. In connection with this book, however, the division of archaeology should be mentioned. Archaeology is a part of cultural anthropology, and it is the study of the remains of man’s material culture—his tools, his weapons, his pottery, his temples and homes—from its first appearance in time, and overlapping the period of reliable written records. Archaeologists dig up history out of the earth, history that was never written down.

There are no dinosaurs in anthropology, for the good and simple reason that anthropology concerns itself with man. Dinosaurs, despite certain comic strips to the contrary, lived many millions of years before the coming of the first man. So we will have to struggle along without the giant reptiles in this book, but they will not be missed.

Man himself is the most fascinating animal that ever existed on the face of the earth.

Anthropology is a young science, as sciences go, but it is a very important one. It is not merely a collection of odd facts about ancient times and quaint customs of the Indians. Rather, it is a technique that helps us to understand ourselves. In a world of atomic energy and warring nations, nothing is more important than learning to control and correctly utilize the vast forces that mankind has at its disposal. If we are to survive, we must first learn to understand.

That is what anthropology is all about.

III: How Anthropology Is Used in This Book.

Science fiction writers are often guilty of extrapolation, but this is nothing to become unduly alarmed about. No extrapolationists have been investigated by the F. B. I., and they are not subversive in any way. When a writer extrapolates, he simply discusses the unknown in terms of the known. For example, no one of you now reading these words has yet lived in tomorrow, unless you have a time machine or two up your sleeve. Nevertheless, you could safely predict a number of things about that tomorrow that you have never seen. You could, for instance, predict that the sun would rise and you would have a better than fair chance of being right. You could go on and predict some of the things that would happen to you—you would go to school, or play baseball, or eat three meals a day, or go fishing down by the river. You have never seen tomorrow, but you can tell with some accuracy what your family will be like, how your family makes a living, what your beliefs and customs will be. This is extrapolation; you are discussing tomorrow in terms of yesterday and today. Inevitably, you will make some mistakes, but you will have a batting average that will be a lot healthier than one produced by mere wild guessing.

How is anthropology used in this book? Primarily by extrapolation, and this is how it works:

Most of what we know about the Neanderthals, or about the later Cro-Magnons, is based upon a relatively few anthropological finds. In some twenty sites in and around Europe, fragments of these people have been found—sometimes only a bit of jaw and some teeth, sometimes almost complete skeletons. Together with these skeletal remains, artifacts have been found, tools used by man.

The Neanderthals lived a long time ago; authorities disagree, as usual, about how long. However, they probably flourished roughly between 100,000 B.C. and 50,000 B.C. No man has ever seen a Neanderthal, and they left no written descriptions behind them. But we have a very good idea not only of what they looked like, but also of how they lived. From their skeletons, scientists have reconstructed their appearance, and these reconstructions have been both painstaking and convincing. There are details that we do not know, of course. For instance, skin color is something that cannot be determined from bones, and body hair vanishes with the passing of the years.

Chipped flint tools have been found with Neanderthal men, so we know a good deal about their weapons. Charred remains have been located, so the Neanderthals had fire. They buried their dead, and supplied the deceased with weapons for use in the hereafter. In one of the caves, a row of cave bear skulls was found, shaped like a shrine. Undoubtedly, the Neanderthals had a religion.

They lived as hunters, according to the evidence, killing and eating the animals of the Ice Age—notably the mammoth, the woolly rhinoceros, and smaller animals. This, in turn, means that they had a language of some sort. Hunting mammoths presupposes group activity, and group activity on that complex level demands a language.

We have small cause to look down upon the Neanderthals as stupid brutes. In fact, ironically, they had bigger brains than we have; some of them having a volume of about 1,625 cubic centimeters. The size of a man’s brain, of course, tells you nothing about how good it was, but the Neanderthals, living as they did in the dawn of man, had a culture that commands respect. The mere accomplishment of survival for that long under those conditions is a very real achievement.

The Neanderthals are so named because the first recognized discovery was made in the little Neander gorge in Germany in 1856. “Thal” simply means “valley.”

The Cro-Magnons were a different kettle of fish altogether. They were true Homo sapiens, who lived in Europe from approximately 50,000 B.C. until about 10,000 B.C. In this connection, it might be pointed out that there were no Neanderthals or Cro-Magnons in America at any time, so far as is known. Man evolved in the Old World, and the Indians who were living in the New World when the first settlers pushed westward had migrated here from Asia across the Bering Strait.

In general, we know almost the same things about the Cro-Magnons that we know about the Neanderthals. That is, we have their skeletons, their artifacts, and so forth. In addition, we have their paintings on the cave walls of southern France and northern Spain, the first great art produced by mankind. They were a gifted people, both physically and mentally, and they lived as hunters on the plains of the late Pleistocene, or Ice Age.

All this is of necessity very general, and suppose we now get down to brass tacks about the extrapolations in this book. This is a work of fiction, and does not claim to be anything else. However, I submit that the picture you will find here of Cro-Magnon man is not a fantastic one and is based on reasonable conjecture. Here are a few examples:

Language. There is no book that you can go to that will tell you anything about the language of the Cro-Magnons; they had no writing, and the spoken word does not last long. They had a language, of course, and probably a rather advanced one, but of what it may have consisted we do not know. Your guess, or mine, is as apt to be correct as any other. In naming the Cro-Magnons, I have simply tried to steer clear of the annoying “Ughs” and “Mo-Ros” that so often clutter up stories of this sort. There is absolutely no reason to suppose that Cro-Magnon names were on the level of animal grunts.

Social organization. Just as in the case of language, you cannot tell much about how a society was put together only by looking at a few bones. We do know, however, that the Cro-Magnons had a hunting economy. Therefore, I have pictured a social organization that fits in with what we know about other primitive hunting groups, such as the Plains Indians of our own country. That, incidentally, is the reason for the introduction of lean-tos into Cro-Magnon times. No such structures have survived, although certain house-drawings have been found on cave walls, but they probably existed. Hunting peoples must follow their game supply—any hunter knows that he cannot simply sit in one spot forever and kill enough game to live on. Caves are not portable, and just as the Plains Indians had their tipis, and the Eskimos their snow houses while on the trail, the Cro-Magnons must have had some similar shelter that they could carry with them.

Songs. Men everywhere have music and song, and I have given the Cro-Magnons a song to sing. We are prone to think of primitive peoples as somehow lacking in human values like laughter and song, but such is demonstrably not the case. I don’t know any Cro-Magnon songs, and neither does anyone else. So I have invented one—but in so doing I have not just spun one out of the air, so to speak, but have instead reworked portions of an Indian prayer and a primitive chant into what I hope is a meaningful song. It is not suggested that this is a Cro-Magnon song, but simply that it might have been something like this.

The list could be extended indefinitely, but to little profit. I hope that these few examples have given you some idea of how the process of extrapolation works in this type of science fiction, and also shown you something of the differences between fact and fiction.

IV: A Bonus, Free of Charge.

This is a work of fiction, and as such its purpose is to entertain. If it gives you a few hours of pleasure, or even keeps you up all night to find out what happens, it has accomplished its mission. If it does not entertain, if it is not fun to read, then nothing else will make it worth your time.

If you do have a good time reading it, and I hope you do, that in itself is something. I also hope, however, that you can pick up a bit extra along the way—a sort of painless bonus. The bonus is free of charge, and you can ignore it if you wish.

For those who are interested, though, I hope that there are a few lessons to be learned from this story, lessons in tolerance and understanding and common humanity. It may be that you will now think twice before you condemn others merely because they live a different kind of life than your own, and you may look back upon the long history of mankind with more appreciative eyes.

It comes as something of a shock occasionally to remember that it has only been some one hundred and seventy-six years since this nation got underway in 1776, and only four hundred and sixty years since Columbus sailed for the New World. Writing itself is only some five thousand years old at best, and in some parts of the world, such as North America, it did not exist until a short few hundred years ago. Man himself has been around a lot longer than that, with all his dreams and his never-ending search for happiness.

If we are ever to understand the last part of the story of mankind, we must understand the first chapters as well—not to mention the later episodes of peoples about whom we know little or nothing. There is a lot of history, and a lot of fascination, yet hidden from our eyes in the gray mists of time.

Ich glaube, das sollte man einfach so stehen lassen.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen